This document is the result of a period of reflection and global evaluation of the experience in the application, development and dissemination of our project for the Reconstitution of the Communist Party over a decade (1994-2003).

Self-criticism

In the process of evaluating our political trajectory we have addressed the examination of some of the pillars over which the Reconstitution Plan was standing, mainly the one related to the character and definition of the ideological premises from which we departed, and the one related to the nature of our organization as a vanguard organization, in itself and in the general context of the present vanguard movement. From this assessment and its consequences has resulted the need to initiate a movement of rectification in our style of work and in our tactical line, in the sense of adapting much more the objective of the Reconstitution of the Communist Party to the real circumstances prevailing today in the communist movement, in the workers' movement and given the present state of the proletarian class struggle.

As for the ideological basis, we have come to the conclusion that basing it exclusively on the study of the classical sources of Marxism-Leninism, adding a summation of the historical experience of the construction of socialism (understanding summation almost exclusively as the purification of tactical and even strategic errors, but above all of errors of a political order), will be totally insufficient from the perspective of the assumption of the proletarian ideology as the starting point of any revolutionary project. In the first place, because our analysis of the October Revolution - to the extent that we have carried it out so far- has led us to adopt a critical position with respect to what we call the October Cycle, regarding many of its factual theoretical constructions (and also to quite a few of its political constructions), from the point of view of their universal and current validity. The work of October has bequeathed us a treasure of revolutionary experiences. However, it has also left us with countless ideological and political elements, inserted in the revolutionary discourse, which are rather children of the practical necessity of the moment or of the conjunctural agreement of Marxism and the revolutionary proletariat with other political or social forces in the face of certain circumstances which, although passing, left a permanent mark on the Marxist discourse without receiving the pertinent purifying criticism once those conjunctures were over. The Marxism that October bequeaths us is thus loaded with resonances of the past along with problematic elements added by the difficulties of each political moment, and drags the alluvial sediments that have been deposited by political alliances, ideological commitments and, not the least times, its deficient understanding and inadequate application. Not everything that has been traditionally understood as Marxism or Leninism was really Marxism or Marxism-Leninism.

It is true that, like any social phenomenon, Marxism as an ideological formation is a historical product, it is determined by its time and by the circumstances surrounding the epoch in which it arises and develops (especially by the degree of development of the proletariat and its class struggle). In this sense, we cannot speak of a compendium of absolute truths, nor of eternal ideas or ex tempore inhabitants of supralunary Platonic worlds, always ready to be embodied in our world at any given time. But if Marxism is not idealism —although dogmatists of all kinds have reduced it to this—, neither can it be associated with social relativism. Certainly, Marxism is the child of an epoch, that of capitalism, and in this sense it is contingent and even conventional; but the fact that it must or can adapt to the demands of social change does not mean that it is in this quality that its potency as an ideology resides, but rather in something permanent: a set of granitic, immovable foundations shaped as clearly defined revolutionary class principles. And it is in these principles where the universal value of Marxism lies, the sphere through which it connects, from the revolutionary practice of the proletariat, with the secular tradition that has kept alive the emancipatory ideal of humanity. Forcing the fine thread that marks the line of equilibrium in the internal coherence of Marxist discourse (for example, between its monolithic principles and the flexibility of its political theses) amounts to distorting it. This happened many times during the October Cycle, which has resulted in a whole conglomerate of theoretical deviations and unilateral interpretations alien to the criteria of the true Marxist spirit becoming part of its current heritage. Nobody can deny, for instance, the importance for Marxism of the relationship between the working class, understood as a mass movement, and class consciousness. We cannot deny the importance of the spontaneous movement of the class, of its struggle of resistance against capital, because then we would deny the materialist basis of Marxism as a theory; however, if we exaggerate this aspect to the point of falling into workerism (practicalism, trade unionism and, on a more philosophical plane, empiricism), we would deny the role of consciousness and, consequently, we will destroy the dialectical basis of Marxism. Both deviations occurred during the past revolutionary cycle -and even dominated it-, especially the second one. What, in short, the October experience shows is that, from the point of view of its development as a guiding ideology of the proletarian class struggle, Marxism has ended up forming a doctrinal body in whose interior cohabit foreign elements whose specific weight ended up disfiguring the profile of its original formulation as a philosophical theory and, after that, weakening the political positions of the proletariat. Consequently, the task of resorting to Marxism as the ideological referent of the revolutionary project offers a difficulty in the form of a contradiction: on the one hand, we have the clear definition of the premises and conceptual categories of the doctrine from its first formulation although this is totally insufficient to face the present tasks of the Revolution; on the other hand, we have a rich, complex and multifaceted theoretical development of Marxism that must be approached critically to separate the wheat from the chaff - what is a true contribution to the proletarian theory, in line with its gnoseological postulates, from what is not. Ultimately, we must conclude that it is not possible to recover Marxism or Marxism-Leninism as an ideological reference without a work of reformulation, in the sense of purification of contaminants and foreign elements that hitherto accompany it—as shown by the different versions that still compete against each other advocated by countless more or less revolutionary organizations— and of critical apprehension of all its development that will let us place that ideological starting point at the height of the demands of the preparation of a new revolutionary cycle.

Secondly, not only is the reformulation of Marxism from itself, so to speak, necessary as an ideological basis, but it is also necessary that this reformulation matches the state reached by humanity’s knowledge. The doctrine elaborated by Marx and Engels fulfilled this condition in its day, and the same can be said of Lenin's contribution. In both cases, there was a reformulation of a received theoretical legacy and in both cases this reformulation was carried out in relation to the progress of scientific knowledge. Naturally, Lenin's qualitative contribution to thought does not have the same significance as that of Marx and Engels: the latter two created a new conception of the world different from the one they inherited, while the former developed an already existing worldview. Nevertheless, it is also important to point out that what Lenin received as theoretical doctrine was not a totally faithful reproduction of the set of ideas elaborated by Marx and Engels, since the Marxism he received was rather the particular reading and adaptation of Marx and Engels' doctrine carried out by European Social-Democracy. The merits and limitations of Lenin's theoretical contribution must be appreciated taking this circumstance into account.

As for the part of the rectification process that refers to our organization as a vanguard detachment, the raising of the ideological requirements has forced us to rethink our political work centered on propaganda and to understand the need to incorporate yet another objective to the work of the vanguard detachment: the construction of communist cadres. The deep significance of the task of recovering the ideological bases of the revolutionary project, together with the result of the assessment of the current situation of the proletarian vanguard as a whole and of our situation in it, has allowed us to understand the insufficiency of the political mechanism structured around the study-propagate axis (to study the principles of communism and propagate them; to investigate the historical experience of socialism and propagate the conclusions; to analyze the conditions of the Proletarian Revolution and spread them, etc.), mechanism that has articulated the fundamental work of all the vanguard organizations until today, including ours, which differs from the others only by the rigor in the application of those tasks and by the content of the political line, but not in the manifest incapacity —due to inertias stemming from the revisionist culture that survived in our style of work— to prepare the deployment in all its amplitude of that line and to arrange the channels that make it possible when said line is incarnated in revolutionary movement. A new aspect in the projection of the communist political work is then required, one which can no longer be limited to adopt the masses, the problems of their revolutionary leadership and their conscious elevation (downward reference) as the only reference. We must recover the reference for Communism as the final objective in our politics, so that the highest objective also plays a fundamental role in our work, from the point of view of the planning of the political objectives and as a spur for the constant self-elevation of the vanguard, a guarantee of long-term continuity of the revolutionary process (upwards reference). To say it in a synthetic way and to summarize, K. Liebknecht's slogan, Study, organize, make propaganda!, which was valid during all the preparatory period of the October Cycle, is no longer sufficient. In the preparation of the next cycle, the problem concerning the relationship of the vanguard with the mass movement or that of the Party with the class, the problem of the means of the Revolution, in short, will not completely fill with content the proletarian policy; it will also be essential to approach the question of the conscious factor, the question of the relationship of the revolutionary subject with the revolutionary objective, the question of the construction of the new starting from the consciousness (something solved with too much spontaneity and improvisation during the October Cycle). During the First Cycle, thought was given above all to how to win the leadership of the masses. Perhaps, the hard competition imposed by the class struggle absorbed all the attention in this task; the fact is that it was too often forgotten to think about where to lead those masses. Proletarian politics, thus, ended up losing its way and nourishing itself less and less on the noble objective of emancipation and more and more on itself and on the pure and simple mass movement (continually falling back on tailism and possibilism).

We will however develop all these aspects concretely in the following pages. What is important to emphasize now is that the reflection on the political tasks imposed by the Reconstitution of the Party has allowed us to become more aware of the nature of the process itself and of the growing complexity of its requirements, even more ideologically and politically demanding than what it may have seemed to us at the beginning, more than a decade ago.

The vanguard today

Before addressing these new requirements which complicate the Reconstitution Plan, we will point out some of a different nature which will allow us to show that it is not only the theoretical and organizational premises which have been modified by the course of history, but also other premises which are objective and of a sociological and political nature, located in spheres far removed from the direct influence of our activity, and which determine to a great extent the nature of the problem of the preparation of a new revolutionary cycle, conditioning from the first moment the way in which it must be approached and the character of the tasks and the instruments needed to fulfill them. We are talking in particular about the point of departure that the vanguard adopts before the revolutionary cycle and, more specifically, about the political consequences that its different starting position in history entails.

It is clear that, during the preparatory stage of the October Cycle, the ideological vanguard of the proletariat was mainly made up of intellectuals of bourgeois social extraction. Hence, the kind of ‘bourgeois ideologists who have raised themselves to the level of comprehending theoretically the historical movement as a whole’1, described by Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto, prevailed. This ideological vanguard assumed and elaborated scientific socialism and the revolutionary program and took them to the workers' movement, merging with it in the form of a revolutionary organization. The tactics of party building during the First Revolutionary Cycle were closely determined by this historical circumstance. Both the working class organizations that played a leading role in the period of accumulation of forces (parties of the Second International) and the party of a new type that led the assault on power were built on that same historical premise, a premise that defined a tactic of political construction (constitution of the Party) based on the association of two fully configured elements, but external in principle to each other. The ideological manifestos and political programs of the revolutionaries were debated, drafted and proclaimed by Marxist circles and subsequently brought to the class in its spontaneous movement. This mechanics of fusion of external political factors had the advantage for the proletariat that the revolutionary theory, as something assumed and elaborated, formed an integral part of its movement from the very beginning. The drawback, however, was that the fusion as a revolutionary class of these two foreign factors crystallized above all in the form of organization, of political apparatus (more agitative than propagandistic and more propagandistic than theoretical), while the problem of the collective assumption of revolutionary theory by the advanced sectors of the workers' movement was incompletely approached and solved. This, naturally, entailed the payment of a high price in the long term; but in the short term, the rapid implementation of the revolutionary movement cleared up any doubts, especially when —as in the case of the party that opened the First Cycle of the World Proletarian Revolution, the Bolshevik party— historical events —rapid rise of the democratic revolution and of the mass workers' movement in Russia— were pressing and getting ahead of them was necessary.

With the October Cycle over, the question arises: does the vanguard at present, in the preliminary period to the next revolutionary cycle, enjoy the same starting position? The answer is no. At present, and from the experience of the last decades (especially since the end of the last great proletarian offensive, at the end of the 70's), there are no declassed sectors of the bourgeoisie willing to gather the theoretical baggage of scientific socialism to contribute it to the workers' movement. There may be isolated cases, individuals who are willing to fulfill this role, but it is no longer a social phenomenon as in the First Revolutionary Cycle. However, the starting problem remains the same: revolutionary theory, as the sum of universal knowledge and the synthesis of the experience of the class struggle of the proletariat, cannot be elaborated within the workers' movement, but outside of it2. Therefore, the mechanism of fusion of external political factors that once transformed the proletariat into a revolutionary class is still in force; but, at present, the proletariat does not dominate those factors: the historical desertion from the revolution by the bourgeois intellectual has left it orphaned of the main one, the vanguard theory. A historically new problem is then posed to the working class in the most pressing way, a problem which it will have to face and solve with its own forces and resources and that consists in replacing the role of ideological vanguard played in its day by the bourgeois intelligentsia. The conscious worker of our times must rise to the position of depositary and guardian of theory, studying, elaborating and assimilating the ideology in order to fulfill the first requirement of the revolution, its fusion with the practical movement. Our epoch is characterized —at least in the imperialist countries— by the fact that the majority of those who fight for the recovery of the objective of Communism and for the recomposition of the revolutionary movement of the proletariat are workers, which obliges us to think that the new processes of revolutionary construction carry for the working class the added burden of replacing those who from the outside brought the ideology necessary for the working class emancipation. The advanced sectors of the proletariat must, therefore and consequently with all that this implies from the point of view of political work, cover the transition that will lead it to leave the spontaneous movement of the class and assimilate the ideology consummating the function of ideological (theoretical) vanguard of the old intellectual, to return, then, to merge with the class as effective revolutionary vanguard. The Reconstitution of the proletarian party must dedicate an ample part of its tasks to satisfy the requirements of this transition, mainly during its first stages. In the new revolutionary era that opens, the contradiction between theory and practice is thus resolved within the working class after a process of split-fusion with its vanguard, a longer process (politically and also, in all probability, in time) than the simple fusion of the First Revolutionary Cycle, but that will allow us to undertake the processes of construction of the Party and Socialism from a deeper vision and with greater guarantees of success.

The complete conquest of the position of ideological vanguard by the most conscious sector of the proletariat -a conquest that implies a whole period of struggles among its various detachments- means a certain retreat from the point of view of the Reconstitution Thesis, since in this political thesis it is presupposed that this position has already been conquered. Nevertheless it has precisely been its application through the Reconstitution Plan which has led us to the conclusion that it is necessary to take a step back in the political expectations and to reconsider or, better said, to consider in a concrete way the problem of the necessary preconditions for the question related to the dialectics of the ideological vanguard-practical vanguard, the question of its unity in the form of the Communist Party, to bear fruit in the best way. We are talking, after all, about how to achieve the unity of these two bodies through the Communist Party. All this implies a longer political path for the Reconstitution process, but, at the same time, a much broader framework to solve, in a more satisfactory way and with greater guarantees than the revolutionaries who led the First Cycle had, the question of always placing ideology in command of the whole process of revolutionary construction and transformation up to Communism. And, in particular, right now, this new perspective gives us a better vision and a greater room to correctly implement the Reconstitution Plan.

Being and consciousness

But there is another aspect in this whole matter that allows us to affirm that, although the requirements for the Reconstitution of the Communist Party today are broader and demand greater effort for their fulfillment, its starting point is situated on a historically superior plane to that of the period prior to 1917. We are talking about the causes and consequences that accompany that abandonment of the vanguard positions by the bourgeois intelligentsia that we have highlighted as characteristic of our epoch. It is not that the Marxist thesis that explains this phenomenon of the passage of certain sectors of the bourgeois intelligentsia to the ranks of the proletariat has lost its validity, a thesis that states that ‘the progress of dissolution going on within the ruling class, in fact within the whole range of old society, assumes such a violent, glaring character, that a small section of the ruling class cuts itself adrift, and joins the revolutionary class, the class that holds the future in its hands.’3; put it simply, this "section" no longer holds, as it did at the time this quote was written, the role of ideological vanguard. Naturally, the process of decomposition of capitalism and its ruling class continues. Perhaps there is no better proof of this than the fact that it can no longer manage the system without the help of the labor aristocracy. Its crisis has provoked the false reflection of a reversal of the process of social decomposition, as if it were affecting more the working class (all the pseudo-debates on the supposed disappearance of the working class or its transformation into a middle class, etc... have this background); but the arriviste declassing of a fraction of the proletariat only demonstrates its vigor and its possibilities for the future, while the growing dependence on its antagonistic class that capital experiences in order to give continuity to its system of exploitation (either because it needs the active support of the labor aristocracy, or because of the revolutionary passivity of the masses, for which said labor aristocracy plays a not negligible role) is evidence of the state of disintegration of the bourgeoisie. Indeed, just as during the period of the decomposition of the Ancient Régime and the political promotion of the bourgeoisie, the fact that some of its wealthiest elements bought noble titles expressed more the rise of the new and future ruling class than the validity of the feudal classes as a political-social reference, the participation of a privileged sector of the working class in the sharing of the cake of capitalist exploitation and domination does not mean that the bourgeoisie maintains its prestige and solid social position, but, on the contrary, it is the sign that gives way, once again in history, to the rise of a new revolutionary class. On the other hand, however, in certain political conjunctures of withdrawal of the Proletarian Revolution, such as the present one, the process of disintegration and declassing of the ruling class slows down, and the social and intellectual abyss between the two main classes opens up, giving the erroneous impression that the defeat of the proletariat in the First Revolutionary Cycle has been definitive and its proposal for progress has lost all value and validity, even for that part of the bourgeois intelligentsia that seeks a way out of the disintegration of the capitalist mode of production. But, we insist, this remains a mirage: the root cause is not that these elements of bourgeois origin are unwilling to adopt the position of the ideological vanguard, but rather that they can no longer do so. For this reason, the contribution of the bourgeois intelligentsia to the cause of the Proletarian Revolution will be more significant in stages following the Reconstitution of the Communist Party and in tasks related to the application and development, in its broad sense, of its Line and Program (and less in the original elaboration of both). It is also for this reason that during unfavorable conjunctures the trickle of bourgeois elements towards the proletariat is reduced or disappears, because the field in which the seeds that they could sow towards the abolition of classes can germinate has not yet been cleared.

The Reconstitution Thesis already noted the importance of paying attention to the historical originality of the proletariat when it comes to understanding the qualitative leaps in social development. The unity of means (class struggle of the proletariat as such a class) and objectives (emancipation of humanity) that this social class bears as a peculiarity when it steps on the stage of history entails global implications for the class struggle as a whole, but also for certain special sectors within the classes, such as the intelligentsia and the educated sectors of the possessing classes. The foresight of social crisis and the need for historical change, whether consciously or unconsciously, whether in a favorable or contrary way, has always been an attribute of these social strata, from Antiquity to capitalism. But here intellectual activity with respect to change is presented outside the process of social transformation; the intellectual movement is alien to the social movement and observes it simply as an object, from an external and passive attitude of a contemplative subject. The stoicism, individualism and social nihilism with which the philosophers of the Hellenistic and Latin schools revealed the crisis of the ancient world, or the rationalist criticism with which the Enlightenment thinkers destroyed the spiritual foundations of feudal society, summarize the way in which the educated elites participated in two important epochs of transition between different societies. Under the rule of the bourgeoisie, however, the philanthropic observer attitude of the social reformers reaches its limit when Marx places the imperative of the transformation of the world above that of its interpretation or simple contemplation. But Marx himself -as well as all the socialists of his time- could not overcome that limit. Before 1917, Marxism is the most advanced critical theory of the epoch (revolutionary critique), it is the highest expression of social consciousness (the vanguard theory, as Lenin defined it), but it has not yet been able to realize itself as a truly transforming theory, it has not yet been able to join the process of social development: far from having merged with the social being in a single historical totality, it still contemplates it from the outside.

The unity between social being and consciousness, a unity that implies the mutual dialectical transformation of both elements and that sets in motion a process of self-transformation (conscious development) of society, will take place with the constitution of the social organism capable of achieving the fusion between theory and social practice, of the social organism capable of giving at the same time a material content to theory and of inducing a conscious direction to historical evolution. This social organism is the party of a new type that Lenin designed in its fundamental features (and which, probably, constitutes his main contribution to Marxism). In the Leninist party of a new type, in the Communist Party, theory, pure intellectual work, is fused with immediate practice in an activity of progressive transformation of reality. The social being here is no longer contemplated, governed or dictated from outside by the conscience; here, we find ourselves before the self-conscious social being in the process of self-transformation and development. Here, finally, the old intellectual who turned into a social reformer, the best legacy of the educated elites of the dominant classes and the last expression of subjective knowledge, of the conscious subject that does not merge with the object, disappears as such, as an independent figure in history. From this moment on this figure surrenders his banner of the standard-bearer of progress and submits to the implacable dialectic of the class struggle: either he joins the revolutionary organism, where he will lose his title of individual intellectual, but will join the collective intellectual who leads the movement of conscious transformation of the world, or else, his stupid narcissist vanity will lead him to place himself at the service of the reactionary classes and the counterrevolution, under the pretext of a pretended intellectual freedom.

Before the revolutionary experience of the October Cycle, being and consciousness developed along parallel channels. Technology, the form of application of experimental sciences to reality, mainly to capitalist production, is the way in which the bourgeoisie has gone furthest in the problem of unifying theory and practice. The representation of reality through objective laws and the abstraction of the world through the rules that govern its movement facilitated the rationalization of experience through the intervention of those laws and rules (science) with instruments inspired by them (technology). Technique, then, would be the point of convergence between a rationalist conception of the world and the rationalization of a world that the subject transforms in his own image and likeness. But this is a spurious method, since the application of technology is based on the principle of verification and reproduction of objective laws, and does not admit any principle of transformation of these laws as reality by the conscious subject, which, in turn, is conceived as a separate entity from the object on which it exercises its activity. On the contrary, from 1917 onwards, when for the first time in history there is a process provoked, led and directed by an ideologically-cohesive and collective political organism (unlike all previous similar processes, which had a high component of spontaneity and were to a large extent the end products of the aggregate of innumerable random events —and never of a single conscious initiative with defined means and ends—), those two parallel channels converge in a revolutionary process of transformation of the social totality, where cognitive activity is no longer an activity of apprehension and verification of reality, but of change of that reality, and where the development of that reality cannot be separated from the constant revolutionization of our conceptual premises, of our conception of the world. The October Revolution opens a new era in which the conscious subject is a social organism with the capacity to transform objective reality in a creative process of integration that will open new stages of development and organization for human communities. After the end of the revolutionary cycle opened by October, the individual intellectual armed with his critical theory is no longer at the starting point of the new cycle: the historical development requires that at the starting point stands the organism capable of clearing the path of social progress through a total transformation of the world, the Communist Party. Historically, the debate on the role of the intellectual in society or in the face of progress has therefore lost its validity: it has expired and it is no longer on the agenda. Having consummated the First Revolutionary Cycle, to raise the question of emancipation means to put in the foreground the problem of the Communist Party, that of its nature and all the questions related to the requirements for its construction.

Taking all this into consideration, we affirm that the preparation of the second cycle is placed on a higher plane in comparison with the First Cycle. The conquest of the position of revolutionary vanguard can no longer be in the hands of a pretended ideological vanguard that has not acquired the capacity to influence the social process, that has not built social links with the class that generates all the wealth and that serves as the motor of society that allows it to exercise a transforming practice. Before 1917, the isolated vanguard nucleus formed by daring intellectuals ready to put themselves at the head of the revolutionary events could still play some role. But the Leninist conception of the party of a new type, its role throughout the historical cycle of the October Revolution and, above all, the work of transformation and new social construction that was forged around that party, demand today that the starting point of any future revolutionary process should be occupied by such a party, exponent of the qualitative leap in the requirements that the preparation of the revolutionary cycle demands nowadays; a qualitative leap that is expressed in the fact that it is no longer enough for the subjective factor of the revolution to present itself as pure ideological vanguard, but it needs to have gone through a phase of socialization, of fusion with the practical movement in the form of the Communist Party. It is for this reason, because the historical experience of the Revolution since 1917 places the proletariat at a higher stage of political maturity, that the complete and most coherent vision of the Communist Party (our Reconstitution Thesis) could only be formulated once the First Revolutionary Cycle was over, applying this experience to the requisites of the next revolutionary cycle.

However, the fact that the intellectual's debate before society and progress is outdated or surpassed does not mean that the intellectual function has ceased to play a role before that progress, a role that the Party must take up again, assimilating and surpassing it in the broader context of the preparation of Communism. This is the background problem faced by the vanguard (including our organization) nowadays, a problem that must be resolved and which implies the necessity, firstly, of conquering the ideological vanguard position (something which is necessary but not sufficient to initiate the Revolutionary Cycle) as the first step towards the Reconstitution of the Party as the real revolutionary vanguard.

Character of the present moment

The most immediate consequences, in the practical sphere, derived from the necessity of reconquering the vanguard position by Marxism-Leninism (and the fact that this reconquest will have to be done by the working class itself) are the following: first, from an organizational point of view (within the vanguard detachments), the necessary promotion of the cultural and intellectual formation of communist militants, beyond the routine initiation programs with which the formal compromise with the proletarian ideology is commonly resolved; in the second place, from a political point of view, the understanding of the fact that no truly revolutionary political line exists or can exist if it is not built on the formation of the vanguard in that ideology, on the reconstitution of its revolutionary theoretical discourse and on its development and application through debate and two-line struggle within the vanguard; the understanding that, nowadays, the field of consciousness —and, therefore, the field of the questions around its class nature, its internal coherence, etc. — is the core from where a proletarian politics is built. In other words, the theoretical and ideological questions occupy the foreground, and will do so for an undetermined period. Since the PCR outlined its Reconstitution Plan (1993), already oriented by this criterion — although, as we have seen and as we will continue to verify, in an insufficient manner— there has not been in all these years any political or social displacement between the classes, nor within the working class including its vanguard sectors, that justifies a displacement of the axis around which the revolutionary political projects must continue to be built (and the political impotence shown by the last important events led by the masses, such as the mobilizations on the occasion of the Prestige case and, above all, those against the Iraq war and the ones that took place after the terrorist attacks on March 11th, have only endorsed this thesis.) The theoretical and ideological problems that the vanguard must solve in the perspective of the Proletarian Revolution and Communism configure that axis, so we can say that, from the point of view of the general proletarian movement and the leadership of its class struggle, we are in a moment of accumulation of vanguard forces.

The sources from which we draw the requirements that must necessarily be fulfilled in order to achieve the goal of Reconstitution are twofold in nature. In the first place, it is the analysis of the consequences of the liquidation at the hands of revisionism of consciousness and of all the development achieved by communism (both as a political line and organization and from the perspective of the organization of the new society). The results of this analysis form the central body of what until today has been our activity (Reconstitution Plan and Reconstitution Thesis) and the theoretical and practical developments that we have derived from it (political line and organizational line). In the second place, the analysis of the political peculiarities of the second revolutionary cycle, especially compared to those of the first one. In this field, even though we adopted the theory of the cyclical development of the World Proletarian Revolution on a historical scale almost since it was established by the Communist Party of Peru, in the context of the formulation of the thesis of a bend in the road (‘tesis del recodo’) for the Peruvian Revolution after the fall of the party leadership in 1990 and the debate around Chairman Gonzalo’s letters, it is now that we are becoming aware — also in the light of certain conclusions drawn from the studies on the construction of socialism in the USSR— of the importance of the comparative analysis of the premises necessary for the commencement of each revolutionary cycle. Thus, regarding the question of the vanguard, we see that, historically, before the First Revolutionary Cycle, it gets organized in short periods of time: from 1895 until 1903 in Russia and, in the rest of the countries, through single constituent acts, which were almost always reduced to the assumption —formal in most cases— of the Komintern‘s twenty-one conditions. As we explained before, the conditions to build the vanguard were completely different to those of today, mostly due to the position adopted by a sector of the bourgeois intelligentsia towards the Revolution and to the presence of a revolutionary movement on the offensive and of an international vanguard organization (the Communist International). These conditions facilitated the fulfillment of the mentioned requisites for the organization of the vanguard party, but also established, in turn, a certain conception in the communist imaginary that caused defects of a strategic nature, like the insufficient ideological split from opportunism (which paved the way for opportunistic policies), and the extremely weak policy in terms of education of cadres among the proletariat, that went hand in hand with the scarce penetration in the ideological problems which are directly related to the construction of the vanguard (and which in the long run weakened the proletarian stance in the two-line struggle within the communist parties). It was from these political constitutions that the communist parties started to consider straight away how to win the masses and how to seize the power, getting involved in class struggle at a large scale. In this situation, the counter-revolutionary events that caused retreats were seen as an accumulation of forces for the whole class, particularly regarding the ties and influence of the vanguard over the masses and, especially, the struggle of the vanguard to preserve the cadres and the ideological and programmatic principles of the party. Today, in contrast, the historical circumstances from which the second revolutionary cycle can be prepared show us that, in its prolegomena, during the stage of the Reconstitution of the revolutionary party, the accumulation of forces concerns mainly the vanguard circles organized around the ideological and political problems related to the development of the revolution and the construction of the party. We are thus not talking about a conservative task, but about a creative one, as the first objective of the Reconstitution is to recover the revolutionary ideology of communism and to build cadres that will bring it again to the forefront of the Revolution.

The circumstances surrounding the formation of what in the heart of the vanguard will consequently serve as the basis for the Reconstitution of the Communist Party show clearly its theoretical and educational background; in other words, the main problems which we now face have this double nature, and the practical problems that we will face will be closely related to the provision of means and the creation of the necessary instruments to solve those problems. Its solution, then, will entail the political strengthening of the vanguard in general and of our organization in particular, since it will mean that we are progressing in the task of reconstituting Communism from the ideological point of view, a process in which the communist militant will find enough spur, inspiration and initiative for his work —let us not forget that the strength of the vanguard resides in its ideology—, as well as a revitalizing source for his organization. Our ideology, with all the problems that surround it nowadays, must then be, in the present situation, the starting point and the purpose of the main activity carried out by the vanguard.

More self-criticism

As it can be clearly seen, the assessment of our own trajectory forced us to perceive, in a more mature and coherent way, the role of ideology and the character of the tasks derived from it; but it has also forced us to improve the way we perceive our practical work and to subject it to a severe criticism; the conclusions drawn from this criticism lead us to rectify certain fundamental elements of our previous mass line, which was the product of two kinds of mistakes: method-related mistakes and conception-related mistakes.

The mistakes related to our method are the ones linked to the analysis of the dialectical elements of the Reconstitution process in its present stage and which led us to separate our theoretical activity from our practical activity.

In particular, the cause of the mistakes consisted, first, in absolutizing the fundamental contradiction that dominates all the process of Reconstitution (the one between the theoretical and practical vanguard); we did not observe this contradiction as the principal one, but as the only one, and we considered the theoretical and practical problems related to the organization of the theoretical vanguard as their principal aspect, while the mass work with the practical vanguard moved to a secondary level. In the second place, we reduced mechanically the tasks of the Plan in its present stage to that dichotomy, dividing them into principal ones (including here the theoretical tasks: formation, investigation, elaboration, etc.), on one side, and secondary ones (or practical tasks: principally the mass work above the propaganda level), on the other. Doing so, we broke the organic unity that must exist between organized vanguard and mass line, divorcing theory from practice in our political line, through a process of internalization of theoretical activity and a process of externalization of our practical activity. The lack of an analysis of the underlying dialectical complex in the process of Reconstitution and the reduction of this complex to its general form, to the contradiction between theoretical vanguard and practical vanguard in which the secondary aspect was presented as something not capable of being influenced by the principal one, as something external to it —because, taken as a whole, as an homogeneous block, as practical vanguard in general, it did not satisfy the political needs of the present stage of the Reconstitution (those of theoretical nature in particular)—, led us to assume the internal activity as something exclusively internal, while the objective of the mass work was more and more perceived as something unrelated to the most urgent political needs; therefore, the practical work was increasingly appreciated as a simple experience, something to consider in the future, when we would start addressing the questions related to the third stage of the Reconstitution (closer links with the practical vanguard integrated in the spontaneous mass movement and development of the Program). The necessary political line, identified with the most theoretical points of the Plan, on the one hand, and, on the other, the mass practice, increasingly seen as a secondary and experimental activity, only useful when the theoretical demands of the Plan were mainly addressed, entailed not only a separation between theory and practice within our political activity, something that emptied our mass line; it also ended up reducing, from a conceptual point of view, our vision of the mass work to the form of mass work in general, without any nuances, with no capacity to apprehend the difference between the different sectors of the proletarian vanguard, which were more and more perceived as a homogeneous and grey block. The increasingly consolidated conception of a mass line applied as mass work in general hence projected its abstract mediocrity over its own object: the average worker of the practical vanguard, the militant of the resistance movement and, especially, the trade union member with class consciousness in-itself became, this way, the prototype of the future communist militant whose consciousness would be won once we took the mass work up again in a more serious way, already armed with an elaborated revolutionary theory (line and principles, the two main products coming from the first two stages of the Reconstitution Plan). Our mass line became useless for the Reconstitution since it became a trade unionist mass line.

The mistakes of our method in the application of the guidelines of the Reconstitution Thesis to fulfill the Plan brought, as a consequence, misconceptions of the same nature as the matters we had been dealing with; in particular, the way of understanding how the course of the Reconstitution can prosper or which are the mechanisms that make it possible and allow its development. More specifically, we didn’t properly understand the nature of dialectic mediation in mass work. This mediation implies that we cannot transform the consciousness of the masses —neither the consciousness of the masses in general, neither the consciousness of the sectors of the vanguard that conform our masses at the moment— in a direct way through the communist ideology; we need the mediation of certain factors and of a certain practice for this subjective transformation to take place.

The misunderstanding of the dialectic mediation is the philosophical form adopted by the spontaneism that began to dominate our method of work, by which we tried to establish a direct and immediate relationship between our organization as an ideological vanguard group and the practical vanguard. This led us to idealist misconceptions, and, when planning our mass work, we put that practical vanguard before us as the objective of our mass line, in a way in which we not only reduced all the contradictions of the Reconstitution stage to one (theoretical vanguard-practical vanguard); we also reduced all the organizational atomization of the theoretical vanguard to our organization. Therefore, we made up an artificial contradiction (Revolutionary Communist Party-practical vanguard) that lacked a material base which could be the object of a scientific analysis and with which we mentally performed our mass work; it was rather an antinomy, a false contradiction.

From the perspective of dialectical materialism, mediation implies the acknowledgment of the interaction and interrelation between elements, of the fact that nothing is immediately identical to itself, but through the other and its contrary; mediation, ultimately, is the acknowledgment of contradiction4. Marxism, therefore, demands from us an analytical effort when dealing with contradictions and interrelations, and it presents itself as opposed to any intellectual and political spontaneism, like, for instance, anarchist direct action.

Contrary to popular belief, direct action is not a call to immediate violence, but a political concept that advocates that those affected resolve their problems directly and by themselves, which implies the negation of all mediation, of any intermediaries between the cause of the problem and the affected, including politics or any external ideology that, from the outside, could influence in its solution. Anarchist spontaneism thus denies the role of any political organization and politics themselves (i.e. political power) as a necessary part of revolutionary practical activity. Moreover, as it rejects any mediating theoretical construction, anarchism is intellectually spontaneist —to the extreme of embracing political nihilism, as Nechayev— and disregards any contribution which does not come from the movement itself. Communism, as a conception that integrates the great contributions of human knowledge, is rejected as a political inspiration because, as an external referent, imposes a hiatus that would separate the subject from the direct path towards the revolutionary objective. Indeed, Communism creates a scientific vision (historical materialism and dialectical materialism) and, from the assimilation of the objective laws that regulate the development of matter, builds the necessary instruments that allow the revolutionary subject to reach its emancipative objective. As we can see, Marxism and anarchism differ from each other from the very beginning, in the way they approach the phenomenon of consciousness. Anarchism rejects the complex problem regarding the development of the proletarian consciousness posed by Marxism, a development that leads to the theory of vanguard, since anarchism assumes that the proletariat will acquire revolutionary consciousness through its economic experience. Logically, the differences between both schools widen with derived topics, such as the revolutionary party or the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, mediating stages which Marxism considers necessary to clear the way between the proletariat and communism.

Marxism follows the etymological meaning of the word consciousness, which is built upon the Latin preposition cum, which means with, and the verb scire, which means to know. Consciousness means, then, with the knowledge, that is to say, consciousness is not the immediate product of the reflex of reality on our mind, as it could be inferred from any spontaneist conception of the world as Anarchism (mechanistic materialism); on the contrary, consciousness is the acquisition with knowledge, with science, of all perception of experience. Marxism thus builds its doctrinal body from science, something that can also be said about all its political instruments. This relation between the real movement and science is the procedure by which the class ideology is presented as the first necessary mediation and as the condition of possibility of said real movement as a revolutionary movement, as a conscious movement led by a vanguard ideology. The return to the scientific-ideological aspect implies a separation from the movement, a projection from itself as a spontaneous movement that compels to address fundamental questions not directly related to the progress of the movement, but necessary to activate its revolutionary aspect (ideological reconstitution of communism —theoretical aspect— and construction of the vanguard —practical and organizational aspect—, first, and Reconstitution of the Communist Party, later). Ideology is what gives us this long-term perspective of transformation and what informs us of the revolutionary potential of the spontaneous social process. That is why, for Marxism, the political strength comes from ideological firmness5, while, for anarchism, ideological representations seldom are of any importance and limit themselves to the opportunities of the movement itself.

Our organization has always been aware, since its foundation, of the importance of the ideological-conscious part and therefore of the particular tasks that came along with it. In fact, the importance given to organizational activities related to this ideological aspect, like the priority of formation of cadres, was the first element that differentiated us from the rest of the organizations that said to follow our same objectives. Nevertheless, as we have pointed out, in the light of the results of our last experiences during the last period, we have become aware of the fact that the ideological-conscious element has an even greater transcendence in the preparation and development of the revolution. We will further develop this later on. What interests us the most now is to underline the importance of the mediation of the elements through which the continuity of the historical revolutionary process is resolved, specially the ideological sphere, whose reconstitution is a mandatory step in order to restore the ideological vanguard position of communism, for Marxism-Leninism to recover the guidance of the workers’ movement; all of this will be impossible without the acquisition of consciousness, of the necessary theoretical instruments through science. This is a basic demand for the construction of the vanguard; without it, we will not be able to educate the masses, and consequently, the fundamental elevation of the second major and mediating element in the revolutionary process, the Communist Party, will also be impossible. We were drifting away in such a way from a deep understanding of the ideological and scientific requirements (also in its practical, educative dimension) of revolutionary consciousness that we were slowly sliding towards what we had already criticized about other organizations (like the Frente Marxista-Leninista de España (Spanish Marxist-Leninist Front) and the Comité de Organización (Organization Committee)). The false contradiction (antinomy) that we had made up between our organization and the practical vanguard, and which we had considered the principal contradiction in the present stage of the development of the Reconstitution process, led us to underestimate, unconsciously but de facto, the way in which revisionism had liquidated our political, ideological and organizational tradition, and, consequently, to overestimate the impact that our political line, in the present degree of elaboration and application, could exert over the current consciousness of the workers that already have class consciousness (in itself). We ended up thinking that there is no intermediate step between solving the main theoretical tasks and reaching the masses that make up the practical vanguard, and that the pure, quantitative development of that theoretical elaboration sufficed, at a given time, to take a leap towards practice as our main activity.

Our limited assimilation of Marxism-Leninism and our extreme focus on our daily tasks made us lose the global picture and forget the meaning of the lessons that Leninism had explicitly taught us (like Lenin’s thesis on winning the masses not just propagandizing the principles of communism, but through the mediation of the practical experience) and those with which we ourselves built such important political bases like the Reconstitution Thesis, which insists precisely in the necessary transitions that make the translation and assimilation of the principles of communism by the masses possible. The successive steps that lead from the Principles to the Political Line, and, lastly, to the Program, constitute the successive links of the chain that allow the assimilation of communism through concentric circles that are increasingly wider, whose scope includes progressively bigger sections of the most advanced sectors of the masses. Each of those transitions requires however a concrete analysis and a definition of the theoretical and practical tasks, as well as a link between them, a mass line. Our mistake, which came from the separation in our minds of the theoretical and practical problems of the Reconstitution as principal and secondary problems, led us to the false conception that these transitions were kept and resolved, fundamentally, in the field of theory, and that there was not any practical activity with the masses linked to it, except, at the most, when we would face the last transition in the search for the practical vanguard and the revolutionary Program. The trade unionist mentality, and thus the false idea that there can only be one, truly real, mass work, exerted —and exerts— so much pressure over our consciousness, that we were already impatiently preparing the third stage of the Reconstitution (the “political-practical” stage of winning the practical vanguard). Eager to address the task we were most familiar with —to work elbow to elbow with the masses—, we had our sight set more in the future than in the present, and with such intellectual attitude we neglected the analysis of the singularities of the current stage. Now we have rectified on this matter and we have tried to rearrange our vision towards the order and interrelation of the contradictions which are at the base of the Reconstitution process. With that in mind, we have gotten rid of the idea that the average union worker, the worker with trade unionist consciousness, must be the main political target for our mass work. The most urgent task from the point of view of a correct mass line, that is to say, from the perspective of the recuperation of the unity between theory and practice in our political work, is that of defining the immediate vanguard circle that we must win for the cause of the Reconstitution and Communism, as well as the environment and the means needed for that. Likewise, and in order to fulfill that unity between theory and practice, in the future we must consider those circles, which are the objective of our mass line, both as an object and as a subject of the tasks of the Reconstitution Plan.

Due to its scientific character, Marxism-Leninism cannot be assimilated neither spontaneously nor directly by the proletariat. Like other sciences, Marxism-Leninism can be initially apprehended only by certain individuals who are predisposed to it, but it requires a series of instruments so that it can become part of the class and its movement. Those instruments are the means through which Marxism-Leninism adapts itself to the language and the intellectual reception of an increasing base of the proletarian masses. If we are allowed to introduce such an analogy, this process is really similar to the one we can observe in the food chain. The food chain is based on the organization of species according to a predatory scale, in which each one of them feeds on its predecessor and serves, in turn, as food to the next species. The trophic chain is regulated by a dialectical process based on the contradiction between organic and inorganic matter; that is to say: the cycle of transformation of one into another. In this cycle, minerals (calcium, phosphorus, iron, etc.) and other substances which are essential for life are transformed into organic matter thanks to the photosynthesis mechanism of plants; when plants are ingested by herbivorous animals, they metabolize those substances thanks to the organic form in which they present themselves; the same way happens when herbivores are hunted by carnivores: the latter will assimilate the basic materials necessary for life in the only way possible for them, that is, not directly, but through the physiology of the herbivore. Something similar happens with proletarian ideology: it cannot be assimilated directly by the class, but through its most theoretically and culturally advanced sectors, which in turn expand their influence to sectors that are even wider and even more linked to the deepest strata of the class; proletarian ideology thus traverses this kind of food chain of communism through which the pure principles of Marxism-Leninism are metabolized until they become comprehensible to the great majority of the proletarian masses, through a successive hierarchy of problems, concerns and demands. In this process, Marxism-Leninism starts by solving the fundamental theoretical problems that the next resumption of the labor movement as a revolutionary movement requires (ideological reconstitution), regaining its ideological vanguard nature struggling, ideologically and politically, against the opportunistic way of resolving these problems. Then, by defeating these opportunistic movements and incorporating the best masses from them, their most honest and valid members, the construction of the proletarian vanguard continues. It is in this way that our mass line, aimed at the conquest of these theoretically advanced circles of the class (theoretical vanguard), considers them as a political objective: to incorporate them as subjects of the Reconstitution.

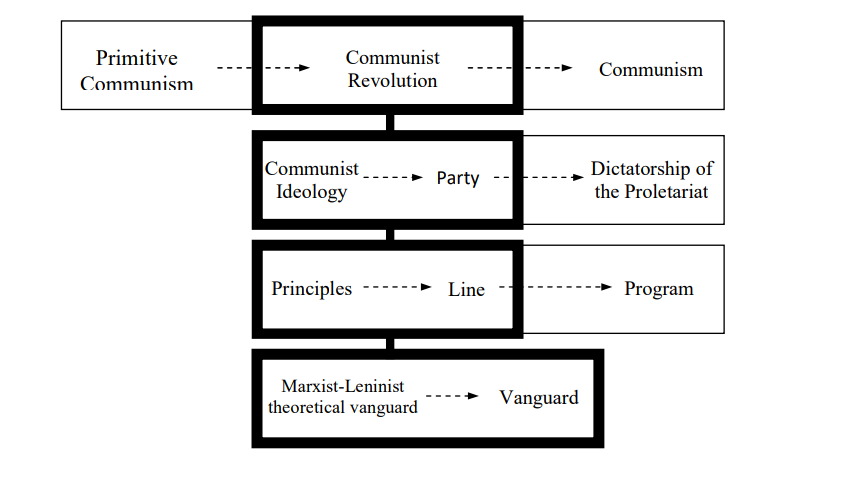

We will unravel, later on, the meaning of all these new aspects that have emerged in our vision of the Reconstitution process. We will now explain broadly, without paying attention to the particular, more or less incorrect way in which we dealt with it, the meaning it acquires from the historical perspective of the social process, in order to finish explaining the problem of mediation and to give a general idea of the role it plays in a process such as the Proletarian Revolution. We will use the following diagram to help us do this:

At the top level we have a summary of the history of Humanity, which, from a certain point of view, can be interpreted as the passage from a classless society, but in a state of need (Primitive Communism), to a classless society in a state of freedom (Communism). This step, however, can only be taken through class society, whose main task is the development of the productive forces; we have summarized this step as Communist Revolution, because all the contradictions of society that must be resolved before reaching a superior historical stage are condensed in it. In a way, the history of Humanity can then be considered as a simple interval towards a stage in which Humanity can develop fully and freely, freed from the servitudes of scarcity and inequality. In reality, it would only be what Marx himself defined as "the prehistory of Humanity".

But the Communist Revolution requires another interim: the construction of those instruments necessary to carry it out. History and the Revolution are certainly made by the masses, yet not directly, but through those instruments. We can see them represented in the second level, and we have focused mainly on them when dealing with the insufficient understanding of the concept of dialectic mediation in our work as organization. These instruments are Ideology, the Communist Party and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, but we have underlined the transition from the first to the second instrument because, likewise, the transformation of Ideology into the Communist Party requires another political interval with its specific tasks dedicated to the reformulation and reaffirmation of the Principles of Communism and its concretion in Political Line and then, in a more profound sense, in Revolutionary Program. This brings us to the last level, where we are, so to speak, nowadays: the necessary intermediate stage to solve the theoretical and practical problems of the ideological reconstitution of Communism and the construction of its vanguard, problems whose solution can be found within the field of two-line struggle carried out at all levels by Marxist-Leninists against all kinds of tendencies that try to lead the proletarian movement, and whose solution is presented to us as a necessary premise for Communism to become the vanguard ideology of the proletariat.

In conclusion, Marxism demands that any enterprise aimed at the emancipation of Humanity must constantly make the critical effort to analyze the dialectical nature of the process in every given moment in order to elucidate the means that its continuity requires as necessary.

The system of contradictions in the Reconstitution process

The dialectical complexity that underlies the Reconstitution process cannot be reduced to a single contradiction, much less be split into its elements to designate one as the main one over the other. And nevertheless, we made both mistakes, as it has been explained. In doing so, we broke with dialectical materialism, for, first of all, it was not a question of elucidating the main and secondary aspects of the contradiction, but of discerning the main contradiction from the secondary contradictions in the process; in the second place, we erroneously separated the two aspects of the contradiction —the first one as principal, the second one as secondary—, that is, we understood it in the metaphysical way of two unites into one, instead of approaching it in the dialectical way of one divides into two. In this sense, we must remember that the Reconstitution Thesis shows that, for there to be a revolutionary movement (at whatever level, before or after the Communist Party exists), the link between the vanguard organization and the masses (mass line) is necessary. This means that there can be no separation between the two aspects of the contradiction (vanguard-masses): mass work must be conceived and applied according to the tasks necessary for the organization of the vanguard and for the fulfillment of its tasks. The priority is therefore to define the content of these tasks at each moment or in each phase of the Reconstitution, the way to organize their fulfillment and the sector of the proletariat on which we are going to rely to carry them out. The vanguard must remain attentive to every change in the content of the tasks throughout the process in order to readjust the organizational relations and links with the masses that each moment requires. This vigilance excludes any dogmatism and any static conception of the various elements that play a role in the Reconstitution, and we fell into dogmatism by unilaterally valuing the main current political tasks only from the point of view of our vanguard organization, without any organic relationship with the masses, and by unilaterally valuing the system of contradictions of the Reconstitution process.

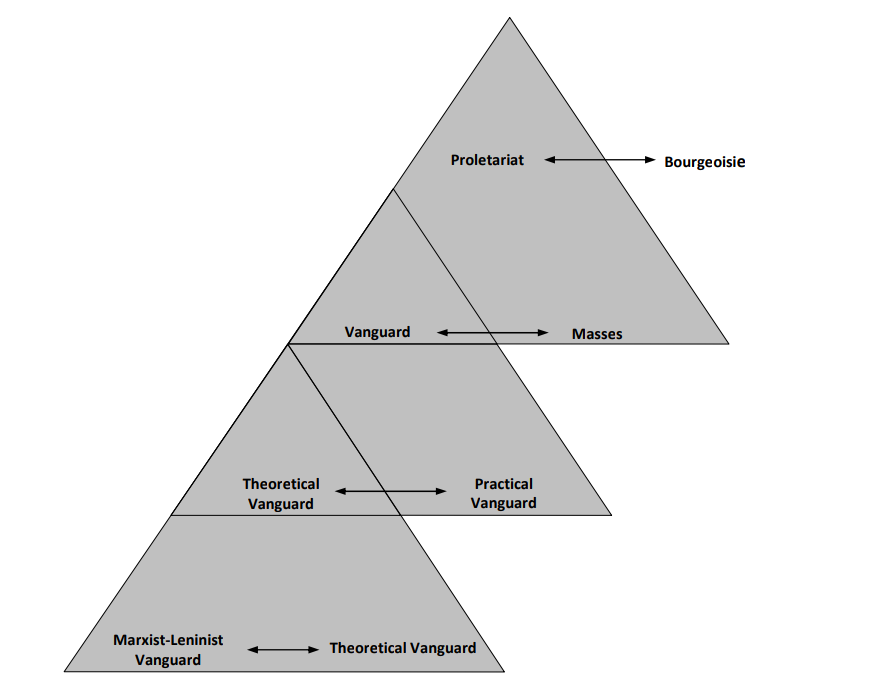

Mao said that “There are many contradictions in the course of development of any major thing”6. This is what we are going to call system of contradictions, the characterization of which is now of the greatest importance in order to overcome the analytical errors we committed, which have led us to unsuccessful political paths. As we know, the Reconstitution Thesis states that the contradiction that governs the development of the process of Reconstitution of the Communist Party is the one between the theoretical vanguard and the practical vanguard. This definition is correct in general because it places at the center of the process its fundamental elements, the union of theory and practice, the idea of merging Communism with the workers' movement, but it takes for granted the overcoming of other contradictions related to the ideological reconstitution of the vanguard. This reconstitution has a mainly theoretical content, and the political problems that accompany it are those that now demand our attention. In any case, it is part of the dialectical system that organizes and hierarchizes the contradictions that structure the Reconstitution process. We now offer this system in its main elements and levels expressed graphically:

Mao also said that “In order to reveal the particularity of the contradictions in any process in the development of a thing, in their totality or interconnections, that is, in order to reveal the essence of the process, it is necessary to reveal the particularity of the two aspects of each of the contradictions in that process”7. In the graphic we can see, in the first place, the order of contradictions that participate in the process of Reconstitution, and the main internal relationships established between them, in a way that its position in the system will facilitate us the discovery of the “particularity of the two aspects of each of the contradictions”, as stated by Mao.

The chart is built from top to bottom, sorted from less to more immediate from the point of view of the need and possibility of development and solution of each of the contradictions in the system. It is formed by the assembly of superimposed triangular units whose vertices show a dialectical element whose position determines its internal relationship with all the elements of the system.

Starting at the top, we observe a triadic module composed of a base on which the contradiction Vanguard-Masses is situated and, at the top, another base led by the Proletariat and the Bourgeoisie. The latter, the bourgeoisie, is left out of the system (that is why it is not included in any triangle), because it is a system that describes the contradictions at the heart of the revolution in its pre-revolutionary historical stage: This is the system of contradictions that the vanguard must resolve and overcome, as a precondition for the great open confrontation between the main classes of modern society. The system, then, describes —as graphically expressed in the diagram— the contradictions that are within or behind the proletariat as a revolutionary class. The Proletariat-Bourgeoisie contradiction can only be resolved with the Proletarian Revolution; but first, the proletariat must successively resolve the fundamental contradictions —from the bottom to the top in the chart— that will make it a mature class to initiate the revolutionary war against the bourgeoisie. The Proletariat as a political entity, on the other hand, develops according to the Vanguard-Masses contradiction (which we have placed at the base of the upper triangle), which is resolved with the construction of the Communist Party (that is, the revolutionary period that goes from the constitution of the Party to the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, when it tackles tasks belonging to this phase of the revolution, such as the construction of the United Front, the Red Army with masses belonging to other classes or the construction of Communism). This is the fundamental contradiction that explains the nature of the proletarian party (Communist Party), and the proper treatment of the unity of its two contradictory aspects is what will enable the political development of the proletariat as a revolutionary class. Finally, the position of the different dialectical elements at the top of the drawing tells us that the struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie is not the central problem at this stage of the revolutionary process (the Bourgeoisie is left out of the system); that place is reserved to the struggle to solve the different problems that are related to the Vanguard-Masses contradiction, and, above all, the problems that affect its main aspect, the Vanguard. In particular, we are talking here about the questions related to the establishment of the necessary links to achieve the unity of this contradiction in the form of a revolutionary process, for which purpose the class struggle is mainly developed within the working class between the vanguard and opportunism, reformism and revisionism, which seek to prevent the political and organizational approach between the masses of the proletariat and its revolutionary vanguard.

The questions that surround the vanguard generally are those that focus the attention of communism in the current period. For this reason, the Vanguard occupies the upper vertex of the next triangular module. The contradiction that, within it, determines its essence is the one that exists between the Theoretical Vanguard and the Practical Vanguard; for this reason, this contradiction occupies the base of this second triangle. The development and solution of this contradiction are linked to the process of Reconstitution of the Communist Party, which is the period that our organization considers to be a necessary preamble to the existence of the party of a new type and its subsequent process of construction. The main aspect of this contradiction is the Theoretical Vanguard, and it is the questions related to the recovery and consolidation of this vanguard that must be solved in order to prepare its fusion with the Practical Vanguard in the form of the Communist Party. For this reason, the latter stays at the top of the last contradiction, the one that is at the base of the whole system: the contradiction between Marxist-Leninist Vanguard and Non Marxist-Leninist Theoretical Vanguard.

One of the main consequences of the summation of the last political period of our organization has been, precisely, the awareness of the existence and importance of the contradiction between the Marxist-Leninist Theoretical Vanguard and the Non Marxist-Leninist Theoretical Vanguard. One of the main causes of our mistakes was to overlook this contradiction and to focus our attention on the superior contradictions of the system, especially the immediately superior (Theoretical Vanguard - Practical Vanguard) which, seen in perspective, dominates the political process of Reconstitution, in which we have placed all our longings. For this reason, we erred at assessing the conditions and possibilities for resolving this contradiction. Since we did not carry out a proper analysis of its main aspect (the Theoretical Vanguard), we did not discover that within it there is a series of contradictions that must be developed. These contradictions can be summarized in the dialectic that must be developed between the Marxist-Leninist vanguard and those sectors of the theoretical vanguard that propose political conceptions, ideas and theses in conflict with it. The solution to this contradiction is the reconstitution of communism as the vanguard ideology of the proletariat. Only if Marxism-Leninism succeeds in hegemonizing the ideology and politics of the theoretical vanguard of the proletariat will it be able to conquer the sectors of the class that lead its struggles of resistance and its spontaneous movement (practical vanguard). It is, therefore, the theoretical and practical problems posed by the two-line struggle within the theoretical vanguard which should be the focus of our most immediate attention from now on, because the contradiction between the Marxist-Leninist vanguard and the Non-Marxist-Leninist theoretical vanguard is the main contradiction of the dialectical system in which the process of Reconstitution is currently situated. Before, we characterized the present moment from the point of view of our organization (deepening in the study of the communist ideology —and which we extend to all the vanguard detachments that claim to be Marxist-Leninist) and from the point of view of the proletariat in general (accumulation of vanguard forces). Well, now we can add too that from the point of view of the vanguard —or, if you will, of the communist movement— we are at a moment in which the implementation and development of the two-line struggle within the theoretical vanguard is crucial in order to bring Marxism-Leninism back to its hegemonic position.

The reconstitution of Marxism-Leninism to its place of ideological vanguard of the proletariat is by no means an exclusively theoretical problem. On the contrary, it can only be the result of that two-line struggle. It would therefore be counterproductive to separate the theoretical from the practical aspects in the current political moment. We must not be fooled by the vulgar, colloquial meaning of words. The fact that the current stage poses problems mainly related to theoretical questions of the revolution does not mean that there is no mass practice to help us in this task. In the same way, the word practice should not only be linked —as we have almost always done— with the activity among the masses of the practical, spontaneous movement; there is also a mass line to solve the problems of the theoretical vanguard, which is none other than the links that Marxism-Leninism must establish with the rest of the theoretical vanguard. Ultimately, it is a question of overcoming the vice (to which our mistakes had led us) of radically separating our theoretical activity from our practical activity, a vice of which we have already spoken; in short, it is a question of restoring the unity of the two aspects of the contradiction, which our analysis has defined as the main one, as a concrete and actual form of theoretical-practical unity. This unit entails redefining the main tasks and the character and purpose of the mass work to be carried out to accomplish them. In other words, what is now presented to us as the fundamental problem is to clarify politically and organizationally the essence and forms of the links, within the theoretical vanguard, between Marxism-Leninism and the rest of that vanguard, and the mass line necessary to elevate them to revolutionary positions.